Pre-WWII Gallery

Curation and Commentary by Eric Greene.

Your generous donation will help us add additional works, and create a more interactive experience to our Galleries.

Paintings are presented in chronological order, with allowances for undated works. Click on an image for more information.

In the post-WWII era throughout the 1970s, despite advances in social justice for various groups of people, the social status of animals remained very low. Any positive depiction of animals was usually represented with a heroism beyond what most (if any) animals could ever achieve, and which tended to be in the service of humans. Such heroes include Lassie, Benji, Rin Tin Tin, Flipper, and even Mr. Ed, whose down-to-earth sagacity was the point of the show.

What is marvelous to see in this collection of paintings from before WWII is that these mostly European and U.S. artists (many of whom often depicted animals in their art) reveal a sensitivity, affection and/or respect between humans and other species in everyday life. This selection of artwork illustrates that a casual, mutual, often loving relationship with other animals is nothing new, but old as time. Most of these paintings pair young people with animals they care for, especially when regarded as family. Look closely and you’ll see that the animals depicted in these paintings see and hear everything, often with greater insight than their human counterparts.

We also find echoes of subject, style, and form. Consider how Ubertini’s (Bacchiacca’s) Portrait of a young lady holding a cat (1525-30) resonates with da Vinci’s earlier Lady with an Ermine (1489-1491). Compare these to Valadon’s Louison and Raminou (1920), where the cat is supported rather than held, and Louison looks at the cat in thought, rather than at the viewer or into the ether. Bloch’s In a Roman Osteria (1866) was inspired by Marstrand’s Italian Osteria Scene, Girl welcoming a Person entering (1847). For Bloch and Marstrand, notice how the animals are present yet excluded from the meal – and all interactions – in a public space. The same is seen in Millais’ Isabella (1849) based on Boccaccio’s Decameron novel Lisabetta e il testo di bassilico, where Isabella is comforting her frightened dog (being kicked by one of her violent brothers). In contrast, there are five paintings of women giving food or drink to animals, especially Reichert’s domestic scene, Feeding Dog, with a young dachshund being fed at the kitchen table: the gender-coded promise of hearth and home.

Consider, too, the transformation of Gérard The Cat’s Lunch to Vallotton’s Squatted woman offering milk to a cat (1919) a century later. Was Gérard a reference for Vallotton? The color palette and the position of the women squatting while giving drink to their cats suggests this possibility. Yet Vallatton’s woman is naked, like the cat, and crouching down on the cat’s level. There is a greater affinity between human and nonhuman animal than in earlier paintings, and the simplified color blocking is a foreshadowing of modern art. As I write and think more about it, I find this to be an important painting.

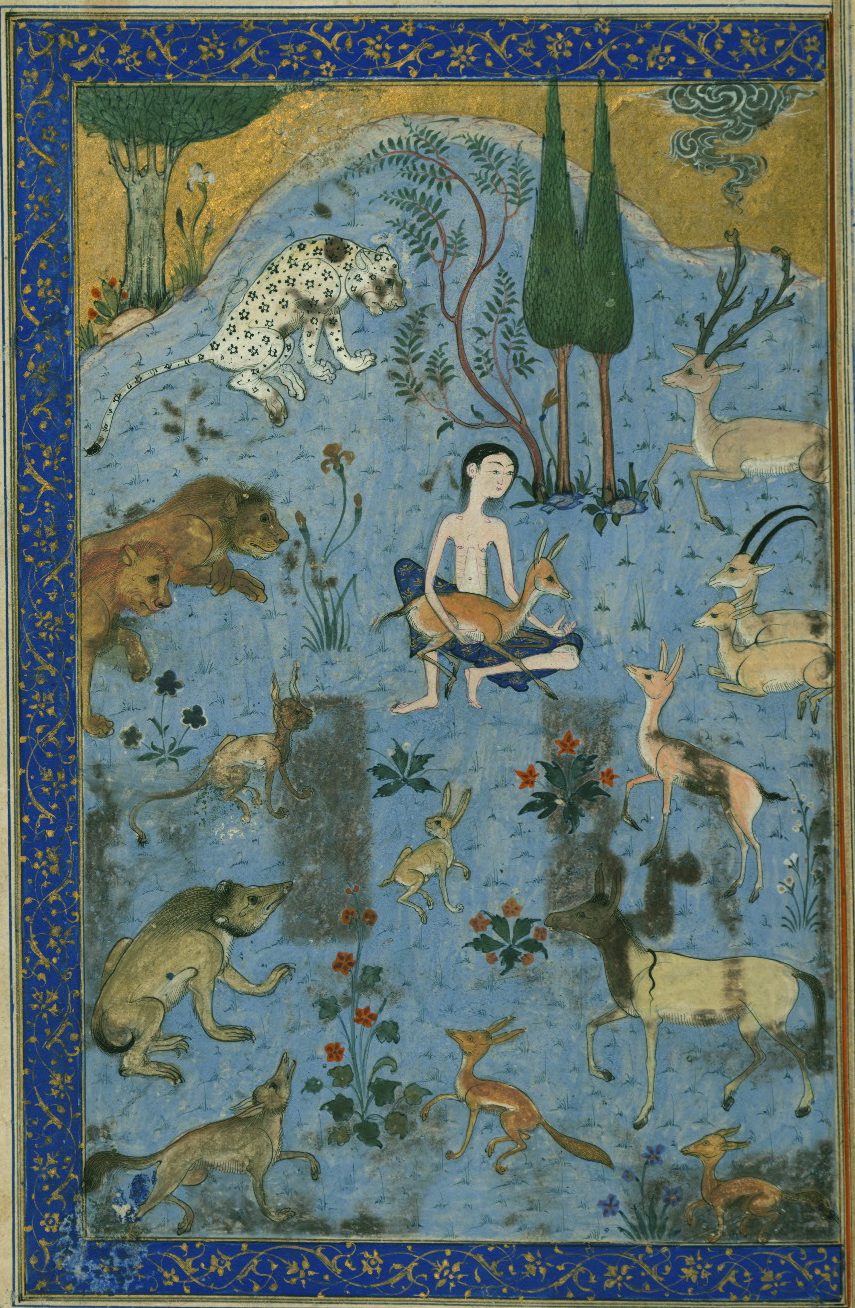

Then we have Rousseau’s almost surreal Le Rêve, a.k.a. The Dream (1910), in conversation with Collier’s Circe (1885). In addition to private and public spaces, these paintings, and others, showcase another sphere – that of wilderness. Still, for Rousseau, cultural attachments and biases vis-à-vis the divan, flute, and multicolored wrap present a choreography of nature and culture.

The 1800s, especially, was a period of anecdotal genre painting, depicting human interactions with other animals in everyday life as well as extraordinary events (a fire, a flood, the Underground Railroad). The strong emotions engendered by these scenes are echoed in the depictions of grief and mourning in our gallery for the Green Pet-Burial Society. At the end of the century, with John Collier’s, Circe, we see the intimacy with reclining women, naked or in nightgowns, with animals. Picasso’s, Lying female nude with cat (1964) echoes Bodarevsky’s Her Favourite (1905).

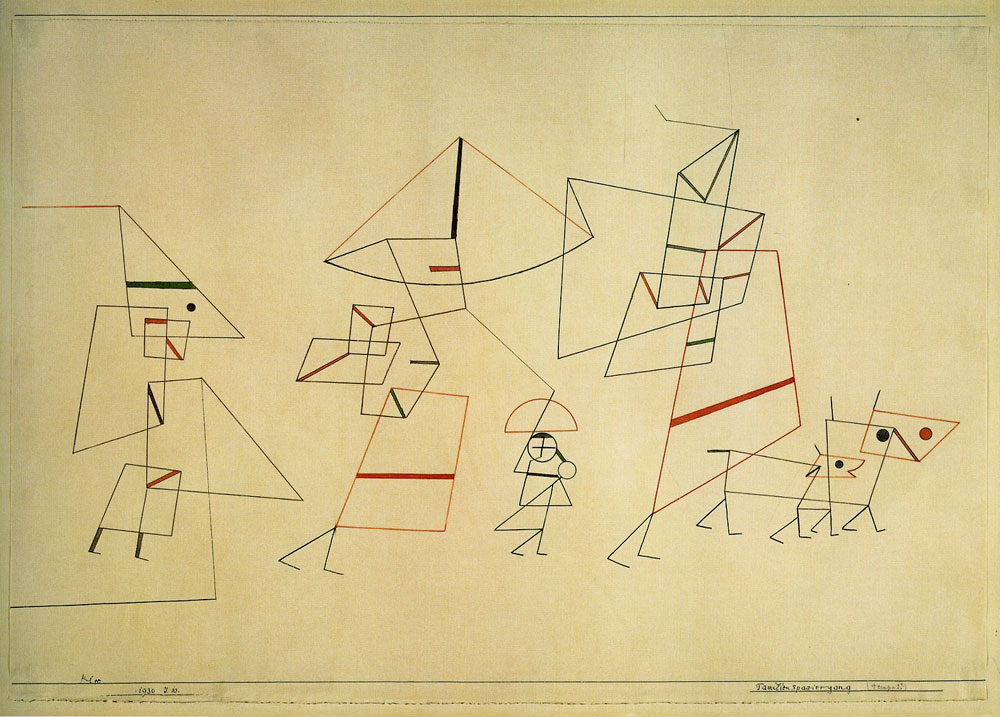

By 1920, Suzanne Valadon’s Louison and Raminou, doesn’t just show the interaction between a human and a cat, but blurs any preconceived notions of difference to heighten their affinity with one another – their sameness in the coloring of the cats fur and Louison’s face, hands, and hair. This is further illustrated by Klee in 1930 by his Familienspaziergang (Tempo II) (Family Walk) – parents, children and dogs are essentialized as stick figures with the same colors. The only difference is their shape.

Throughout this brief history of painting, we find humans either bundled up in clothing, which in many ways defines their character and adds tension to the scene, or they are as naked and free as the animals in their midst (except for Sorolla’s horse; horses are, unfortunately, often tethered). In Klee’s painting, their essence is released, transparent, unencumbered by clothing or bodies.

What other parallels, contrasts, and meanings do you see in this collection?

We continue to expand our galleries – please visit again.

updated April 12, 2025